Douglas B. Marlowe, J.D., Ph.D.

Community corrections officers spend 10 to 40% of their workweek administering and responding to drug and alcohol tests (Alemi et al., 2004; Reichert et al., 2020). They do this because 30 to 50% of probationers and parolees have a moderate to severe substance use disorder (Fearn et al., 2017) and relapse to substance use is one of the greatest predictors of criminal recidivism, increasing the odds of a new arrest by two- to four-fold (Bennett et al., 2008; Kopak et al., 2016a, 2016b). Drug and alcohol testing are believed to improve outcomes by deterring new use, identifying persons in need of substance use treatment, providing objective evidence of treatment progress, and incentivizing adherence to supervision conditions.

Unfortunately, community corrections officers have little guidance on how to administer drug and alcohol testing regimens. Studies in treatment-oriented programs such as drug courts have found that more frequent testing was correlated with significantly higher treatment completion rates and lower illicit substance use and criminal recidivism (Cadwallader, 2017; Carey et al., 2012; Gottfredson et al., 2007; Kinlock et al., 2013; Kleinpeter et al., 2010); however, comparable research has not been conducted in traditional criminal justice programs, such as standard probation or parole. Frequent testing might be ineffective or counterproductive in traditional settings by increasing technical violations, punitive sanctions and reincarcerations. Intensive surveillance without concomitant treatment has been shown to increase failure rates in probation and parole contexts (e.g., Petersilia & Turner, 1993).

No information is available on how often testing should be performed to achieve the most effective and cost-efficient outcomes, when it is appropriate to reduce the frequency of testing, and whether testing should be conducted on a random basis. Once participants have achieved a stable period of abstinence, continued testing may yield diminishing returns and waste valuable resources. Moreover, although it is logical to assume that random testing makes it harder for participants to evade detection, not one empirical study was identified that has examined this hypothesis. Random testing may not be required at higher testing frequencies because the likelihood of detection is already sufficient. Conducting random testing multiple times per week may interfere with participants’ life experiences, potentially leading to higher no-show rates for testing or other negative outcomes.

Current Study

To shed light on these issues, my colleague, Victoria Pokhilko, and I examined chart records devoid of client-identifying information on approximately 2.4 million test specimens delivered by 110,936 justice-involved individuals and analyzed by Averhealth, a nationally certified drug and alcohol testing laboratory. [A manuscript detailing the methodology and findings is under review.] Referrals for testing came from 944 criminal justice programs in 24 states and included traditional criminal courts, pretrial, probation or parole programs (83%) as well as specialty treatment courts (17%). Most tests examined urine (~60%) or breath samples (~40%). The protocol was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board and received a consent waiver for use of deidentified data.

We compared the percentages of tests that were negative for all substances analyzed by the scheduled frequency of testing and whether testing was random or prescheduled. Analyses were performed in 3-month increments up to a maximum duration of 12 months, after which few participants were still being tested. We performed analyses both by treating no-shows for testing and diluted or adulterated specimens as missing data and by assuming them to be substance positive. The results were highly comparable; therefore, outcomes are reported herein assuming missing or adulterated specimens to be positive. Because persons are most likely to no-show for testing or deliver a tampered specimen when they used illicit substances, this approach is most likely to approximate actual substance use outcomes. Finally, we conducted analyses separately for traditional community corrections programs and specialty treatment courts.

Results

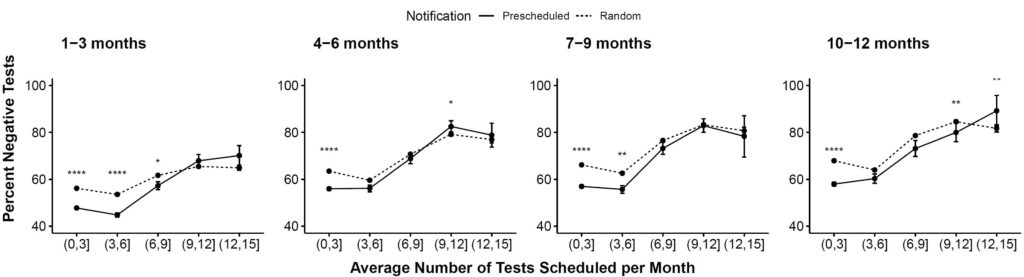

The following figure compares mean percentages of negative test results for random vs. prescheduled testing regimens by the average monthly frequency of testing for the entire sample. The four panels of the figure depict outcomes over consecutive 3-month intervals.

Figure 1. Drug and Alcohol Test Outcomes for Random vs. Prescheduled Testing by the Average Frequency of Testing and Length of Enrollment

Figure 1 notes: Frequencies on the x-axes are expressed in interval notation; for example, (0,3] = testing was scheduled an average of > 0 and ≤ 3 times per month. For each period of enrollment, main effects for the frequency of testing and random vs. prescheduled testing as well as their interaction are significant at p < .0001. Pairwise comparisons between random and prescheduled regimens: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. ****p < .0001. Error bars represent standard deviations.

The following findings can be readily discerned from the figure:

- Increased frequency of testing was correlated with significantly higher rates of negative test results at each 3-month interval (all p values < .001).

- Outcomes plateaued when testing reached an average frequency of approximately nine times per month, which translates loosely to about twice per week.

- Better outcomes from more frequent testing persisted throughout the first 12 months of supervision.

- Random testing was associated with significantly better test outcomes than prescheduled testing when conducted an average of approximately 6 times per month or less often (p < .001); however, outcomes tended to converge at higher testing frequencies. Thus, random testing may not be required when testing is performed more than 1 to 2 times per week.

Treatment Courts vs. Traditional Programs

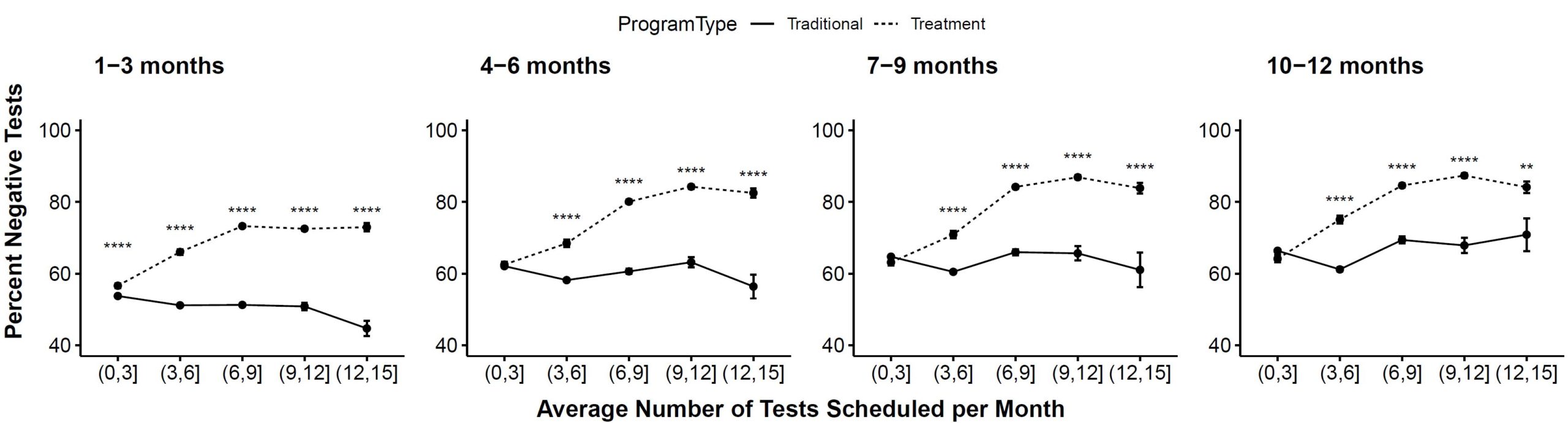

Better outcomes at higher testing frequencies may have been influenced by an outsized impact from treatment courts. The traditional community corrections programs tested the majority of their participants approximately 1 to 6 times per month, whereas treatment courts tested many participants at higher frequencies. The following figure compares test outcomes by the frequency of testing for traditional vs. treatment court programs.

Figure 2. Drug and Alcohol Test Outcomes for Traditional vs. Treatment Court Programs by the Average Frequency of Testing and Length of Enrollment

Figure 2 notes: Frequencies on the x-axes are expressed in interval notation; for example, (0,3] = testing was scheduled an average of > 0 and ≤ 3 times per month. Post hoc comparisons of treatment courts vs. traditional programs: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. ****p < .0001.

Results reveal that higher frequencies of testing were associated with better test outcomes for treatment court participants, but not for participants in traditional community corrections programs where outcomes remained relatively flat or possibly declined at the highest testing frequencies. One possible explanation for these findings is that testing was typically conducted less frequently in the traditional programs and more frequent testing may have been reserved for the highest risk or poorest performing individuals. Another possibility is that frequent testing may be associated with better outcomes when combined with intensive treatment and other services, such as those provided in treatment courts, but may be ineffective or counterproductive in traditional settings where treatment is often less available and positive tests may incur unduly punitive sanctions such as jail detention. More research is needed to understand how testing should be integrated with treatment and other services to optimize criminal justice outcomes.

Discussion

The correlational design of this study should have stacked the deck against finding better outcomes for more frequent drug and alcohol testing. The more often testing is performed, the more likely substance use will be detected. Staff are also likely to have assigned higher risk or poorer performing individuals to more frequent testing regimens. This would be expected to bias the results in favor of more positive tests for frequent testing. Finding the opposite relationship suggests there may be a robust relationship between intensive drug and alcohol testing and better test outcomes. These findings must, of course, be confirmed in prospective controlled trials; nevertheless, they suggest that intensive drug and alcohol testing may be an important component of effective community supervision.

The Critical Role of Treatment

More frequent testing was associated with better outcomes in treatment courts but not in traditional community corrections programs. As was noted previously, this may be attributable to testing being performed less often in the traditional programs, with frequent testing being reserved for the highest risk or poorest performing individuals. More likely, frequent testing was associated with better outcomes when combined with the full panoply of treatment and supervision services delivered in treatment courts, such as substance use treatment, routine court hearings, and graduated incentives and sanctions. Frequent testing may offer minimal benefits when positive test results are met with harsh sanctions rather than serving as the basis for assigning or adjusting indicated treatment services.

Smart Testing

Unfortunately, chart information is unavailable on participants’ clinical diagnoses, criminal histories, or risk and need assessment results. Therefore, the findings cannot inform us about “smart testing” approaches, in which testing protocols are matched to participants’ risk and need levels or previous response to treatment. For example, although twice-weekly testing was found to be the most efficient schedule in this study, this may have reflected an averaging of effects across different risk levels. Testing three times per week may have been more effective for high risk participants and testing once per week may have been more effective for low risk participants, leading to an average, but potentially misleading, apparent benefit of twice-weekly testing. Random testing may also have been more impactful at higher testing frequencies for high risk or high need individuals. Further research is needed to understand how drug and alcohol testing should be tailored to participants’ risk and need profiles to achieve the most effective and cost-efficient outcomes.

Public Safety Outcomes

This study examined drug and alcohol test results as the outcome variable. No information is available on participant’s criminal justice outcomes, including completion rates on community supervision and re-arrest or re-conviction rates. Although studies suggest that reducing substance use is likely to reduce subsequent recidivism (Bennett et al. 2008; Kopak et al., 2016a, 2016b), future research should examine whether lower positive test rates do, in fact, correspond with better public safety outcomes.

Conclusions and Invitation for Comment

Frequent and random drug and alcohol testing is designed specifically to increase detection of illicit substance use, yet we found that positive tests were less common using more rigorous testing protocols. Other investigators have reported similar findings (Cadwallader, 2017; Carey et al., 2012; Gottfredson et al., 2007; Kinlock et al., 2013; Kleiman et al., 2003; Kleinpeter et al., 2010). Results differed between traditional community corrections programs and treatment courts, suggesting that testing may only enhance outcomes when integrated with other needed services. These findings merit consideration by criminal justice professionals. Comments are invited from the field concerning the potential implications of these results for effective community corrections practices and recommendations for further research to better understand the role of drug and alcohol testing in correctional rehabilitation.

References

Alemi, F., Taxman, F., Doyon, V., Thanner, M., & Baghi, H. (2004). Activity based costing of probation with and without substance abuse treatment: A case study. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 7, 51-57. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-15814-002

Bennett, T., Holloway, K., & Farrington, D. (2008). The statistical association between drug misuse and crime: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.001

Cadwallader, A. B. (2017). Swift and certain, proportionate and consistent: Key values of urine drug test consequences for probationers. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(9), 931-938. Retrieved from https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/swift-and-certain-proportionate-and-consistent-key-values-urine-drug-test-consequences-probationers/2017-09

Carey, S. M., Mackin, J. R., & Finigan, M. W. (2012). What works? The ten key components of drug court: Research-based best practices. Drug Court Review, 8(1), 6–42. Retrieved from https://npcresearch.com/publication/what-works-the-ten-key-components-of-drug-court-research-based-best-practices-3/

Fearn, N. E., Vaughn, M. G., Nelson, E. J., Salas-Wright, C. P., DeLisi, M., & Qian, Z. (2016). Trends and correlates of substance use disorders among probationers and parolees in the United States, 2002-2014. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 167, 128-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.003

Gottfredson, D. C., Kearley, B. W., Najaka, S. S., & Rocha, C.M. (2007). How drug treatment courts work: An analysis of mediators. Journal of Research on Crime & Delinquency, 44(1), 3-35.

Kinlock, T. M., Gordon, M. S., Schwartz, R. P., & O’Grady, K. E. (2013). Individual patient and program factors related to prison and community treatment completion in prison-initiated methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 52(8), 509–528.

Kleiman, M. A. R., Tran, T. H., Fishbein, P., Magula, M. T., Allen, W., & Lacy, G. (2003). Opportunities and barriers in probation reform: A case study in drug testing and sanctions. California Policy Research Center, UC Berkeley. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0238v37t

Kleinpeter, C. B., Brocato, J., & Koob, J. J. (2010). Does drug testing deter drug court participants from using drugs or alcohol? Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 49(6), 434–444.

Kopak, A. M., Hoffman, N. G., & Proctor, S. L. (2016a). Key risk factors for relapse and rearrest among substance use treatment patients involved in the criminal justice system. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 41, 14-30. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12103-015-9330-6

Kopak, A. M., Hurt, S., Proctor, S. L., & Hoffman, N. G. (2016b). Clinical indicators of successful substance use treatment among adults in the criminal justice system. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14, 831-843. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11469-016-9644-8?shared-article-renderer

Petersilia, J., & Turner, S. (1993). Intensive probation and parole. Crime and Justice, 17, 281-335. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1147553

Reichart, J., Weisner, L., & Otto, H. D. (2020). A study of drug testing practices in probation. Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. Retrieved from https://icjia.illinois.gov/researchhub/articles/a-study-of-drug-testing-practices-in-probation

Conflict of interest attestation: This research was sponsored by Averhealth, which performed the laboratory tests for the study. Douglas B. Marlowe is a paid consultant for Averhealth.